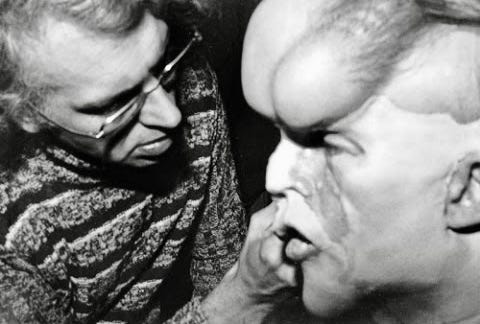

Christopher Tucker, 1946-2022

Remembering my old friend, a mad wizard of make-up effects.

I just discovered that my friend Christopher Tucker died, a week ago, after a short illness.

We last spoke early November, and for a while now, I'd been meaning to call him. To catch up on his latest home and health dramas, to offer advice he'd never take, and then listen, sometimes impatiently, but always with great affection, as he'd regale me with stories he'd shared many times before. Memories of a starry, bygone era of glamour and excitement. Ripping yarns of conflict and drama. Hilarious tall tales of exploits and mishaps. And technical stuff I rarely completely grasped.

I was really very fond of him. He used to call me "Dear Boy", and once or twice asked me not to die as most of his friends had done just that. Though he mainly liked to talk about himself, occasionally he'd ask me how exactly I made a living. I'm not sure I ever answered that to his satisfaction.

I didn't know Christopher when he was famous and at the top of his game. Ours was more an Ed Wood/Bela Lugosi sort of relationship, and the man I came to know felt that, in his old age, the world had rather passed him by. The fact that he's been dead for more than a week now, and really nothing's been written about him online save for a few personal tributes on social media, proves he was right. But in his day, he was a legend, as famous an effects man as there ever was, a unique, inventive and inspired artist who lived, what I call, a Great, Big British Life.

He was a man you'd describe, first and foremost, as eccentric, and by all accounts, that wasn't something that came with age. Christopher was a man who'd say what he thought, and do what he wanted, and if you had a problem with that, well, it sucked to be you.

The first time we met, actually the only time we ever met face-to-face as he lived in far away Pangbourne and wasn't easily mobile, he took one look at me and told me I was fatter than he'd expected.

Sometimes he'd complain about people who'd wronged him, though to me it was clear he'd been the difficult one. He could be gruff, rude and gloomy, stubborn and blinkered. But also he had considerable charm and an impish wit. And fierce talent, of course.

In his heyday, in the UK, Christopher was the go-to make-up effects genius of his age. Had the Academy introduced their make-up effects Oscar a year earlier, he'd surely have won it for his ground-breaking work in 1980's The Elephant Man. He was always pretty sore about that oversight, and deserved better.

It was The Elephant Man that brought us together.

A few years ago, during the first lockdown, I started working with my friend Howard Berger on our first book together, Masters of Make-Up Effects. An elder statesman of the industry, a contemporary and friend of Dick Smith, Christopher was high on our interview wish list, and we were thrilled when Neill Gorton facilitated an introduction.

Unlike every other interview for the book, which was quickly arranged and conducted, Christopher's took a rather more circuitous route, with a handful of preparatory phone calls leading up to our big chat, followed by scores of supplemental conversations. Usually Christopher would just call me out of the blue and start talking. I learned to have a digital recorder ready and always within reach as every time we spoke, he'd remember something else. Fascinating new details, which he called pearls.

He was excited to be a part of our book, a celebration of make-up art and artists, though for sure he felt it should have been all about him. Certainly he was character enough for a book of his own. He told Howard and I how David Lynch, John Hurt and the producers of The Elephant Man had begged and pursued him to create the movie's signature make-up, and how he only agreed to do it on the condition that he be left alone to create it in his home studio. That no one be allowed to see it ahead of shooting, or even call him for updates. Indeed, the first time that anyone beyond he and Hurt ever saw the make-up was when they arrived at the studio to shoot the first scene it featured in.

Christopher was also responsible for designing a handful of cantina aliens in Star Wars (1977), including the character later dubbed Ponda Baba, though at school, as kids back in the Seventies, we knew him only as Bumface. I once told him about that and he looked at me as though I was talking complete gibberish.

The Meaning of Life's (1983) explosive Mr Creosote was another memorable creation of his, as was the startling werewolf transformation from The Company of Wolves (1984) - the one good bit of that movie that everyone remembers. Though Christopher's work in The Elephant Man, The Meaning of Life and Star Wars is well documented in our book, we ended up cutting the following story for various reasons, but it's classic Chris, and I'm happy to be able to share it with you here:

"The werewolf transformation in The Company of Wolves had to be unlike anything that had come before. That's what everyone always wants: for you to come up with something completely original, every time!

"When they hired me, I asked them what they wanted. And Stephen Woolley, the producer, told me, "We want a scary horror film. Something really frightening.'

"I came up with this scene where the man's flesh peels off and the wolf's muzzle bursts out of his mouth. The one thing I wasn't aware of was that the director, Neil Jordan, actually imagined he was making this delicate little child's fantasy film. Certainly that wasn't communicated to me.

So when Neil walked onto the set, and saw this skinned man I'd produced, all bloody and raw, he was absolutely horrified.

"He cried, 'What have you done with my little fillum?!'"

A lesser-known achievement of his was designing the prosthetic penis worn by Daniel Arthur Mead, a porn star better known as Long Dong Silver. And Christopher made a packet from Andrew Lloyd Webber's The Phantom of the Opera, as having designed the original Phantom make-up, he enjoyed years of repeat business, producing the prosthetics worn by every Phantom since Michael Crawford, in every production of the show around the world.

As an elderly man - the man I knew - Christopher had nothing but troubles and worries, and it's sad his life ended that way, but honestly he was the architect of most of his woes. He just couldn't be helped. Wouldn't be helped. It was a source of significant frustration for me, as I came to care about his well-being, that he rejected every positive course of action I ever suggested. Ultimately though, my wife Ruta gave me the best possible advice. "Stop trying to fix him," she told me. "Just be his friend."

So that's what I did. Rather than talk about now, we'd talk about then. Retreat into his glorious, storied past, and there was joy for him in that.

Sometimes, he'd laugh at his own crazy quirks. Like the months he worked with Gregory Peck on 1978's The Boys From Brazil, yet every day, inexplicably, called him Cary by mistake.

"Christopher," Peck pleaded with growing impatience. "I'm not Cary Grant. I'm Gregory Peck."

Once I mentioned to him that a freelance employer of mine owed me money, and he was reminded of the time a French producer likewise withheld funds from him. The producer insisted he'd soon settle the debt, but Christopher wanted cash, not words. Eventually the producer sent his son to the UK with a letter from a prominent French bank declaring that yes, he was good for the money, and that Christopher would eventually, definitely get paid. But eventually wasn't good enough, so Christopher, noticing the son was interested in make-up effects, invited him to stay with him for a few days, and watch him work. After a time, the producer called Christopher, asking if he knew where his son was, and why he hadn't yet returned to France. In response, Christopher declared he was holding him to ransom, and that only after he'd been paid what he was owed, would he allow the boy to leave. At which point, he was, of course, paid in full.

Standing up for yourself, no matter what it took, was a big part of what Christopher was all about, and though I've not yet resorted to kidnapping, certainly his example inspired me to be bolder.

My favourite story of his involved a rollercoaster cab ride around the mountains of Italy. Sitting beside his wife, Sinikka, and behind the driver, Christopher asked him to slow down and drive with greater care. The driver didn't react. His request ignored, Christopher asked again, but this time, angrily. Again, there was no response. At which point Christopher reached out and, with both hands, grabbed the driver by the throat. Squeezing, he screamed something to the tune of, "If you don't slow down and drive more carefully, I will kill you."

That did the trick. The remainder of the journey was smooth as butter. "So you stopped strangling him?" I asked. "Certainly not," said Christopher. "If I'd let go, he might have started driving like a lunatic again. So I held him tightly by the throat until we reached our destination, and then the instant we were out of the car, he sped off. He didn't even wait for me to pay him."

I'm going to miss my old friend.

Thank you for posting this, I had no idea he had died. I once visited Christopher’s “house” in the woods at Pangbourne when I was 16. Like you said, he was gloomy, gruff and rude at times, and as a budding fx wannabe he kind of poked a hole in my dreams by warning me off the industry! But to see his room full of plaster cast faces was amazing, and he will always remain in my memory as a career/life-shaping person.

Great article Marshall. I know Christopher considered you a friend in his final years. You were there for him, listening to what he had to say. Good man Marshall! We will all miss Christopher as those who grew up n the 80's, worshipped him, and now these days, he's little known. It is up to us to keep his memory and contributions to the film industry alive by retelling tales and stories of him. Thanks pal!