Scary Tales

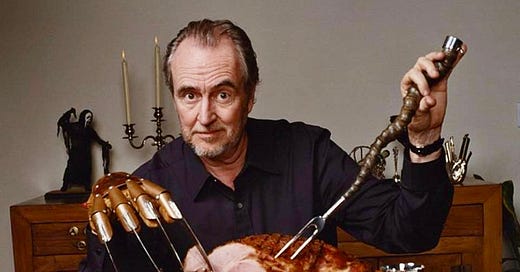

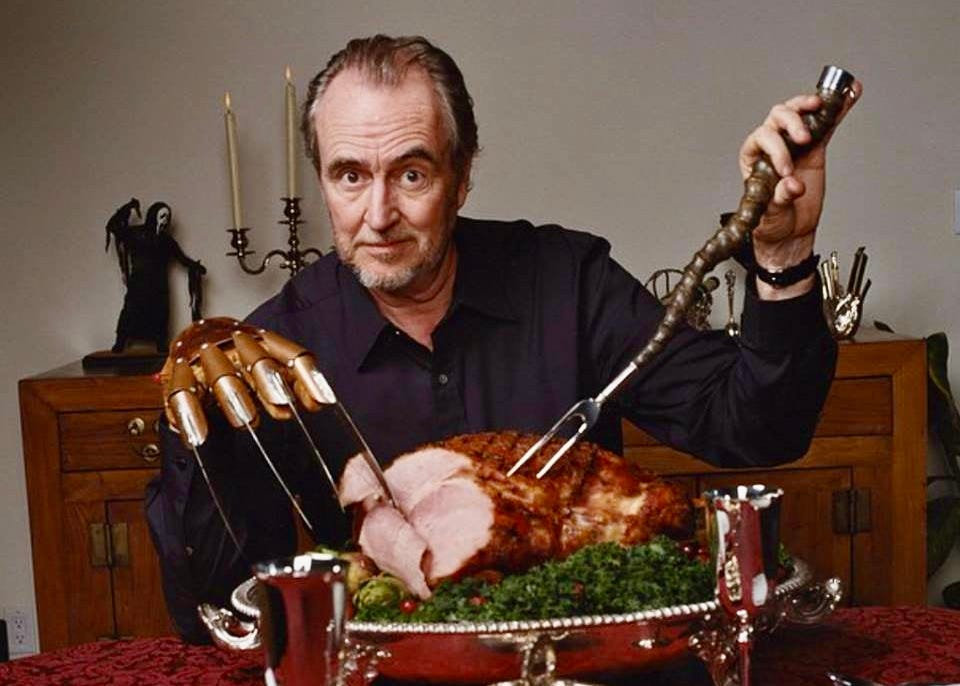

The Master of Maniacal Horror, Wes Craven waxes lyrical on his life, career and philosophy of fright.

According to Pablo Picasso, the chief enemy of creativity is good taste. If that’s the case, then surely The Last House on the Left (1972) is one of the most creative films of all time. Described by Peter Nicolls in his book Fantastic Cinema as “…one of the most brutally sadistic exploitation movies ever filmed”, it also has the dubious distinction of being the lowest rated film - out of several thousand - in Steven Scheuer’s excellent guide, Movies on TV. Given this extreme reaction, it was perhaps inevitable that Last House would ultimately become a cult favourite, making several million dollars since its initial release in 1972 - all for an initial investment of $90k.

Not bad for a first movie, a blistering debut effort from director Wes Craven, who sadly passed away in 2015, though not before carving for himself a unique niche in the realms of the horror movie, from fan-favourite Freddy Krueger to the tongue-in-cheek Scream seres. I was lucky enough to interview the late legend some years back, and I’m excited to share our chat with you here:

Following The Last House on the Left with the classic The Hills Have Eyes (1977), in which a family, stranded and alone in the desert, are attacked by a savage band of mutants, Craven established himself not only as an intense horror moviemaker, but also as a man with something to say.

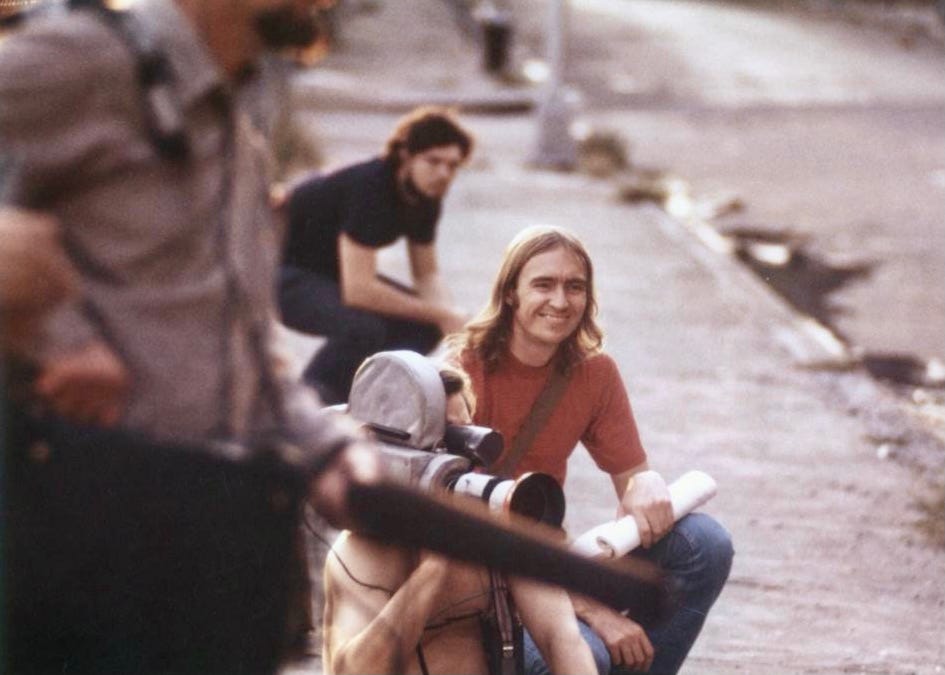

Raised in Ohio by bible bashers, Craven led a serious, academic life to the extent that he’d never even seen a film prior to his departure for college. Concluding his formal education with a graduate degree in writing and philosophy, Craven returned to school, this time as teacher, and it was during this time that he discovered, to his surprise, that he fancied a crack at filmmaking.

“It wasn’t until I was about 28 that I decided I wanted to make films. Before that I had wanted to write short stories and novels, but filmmaking jumped out of the bushes at me and, while I was at teaching college, I bought a camera without thinking much about it and started making movies. Then, at the end of that year, I quit, went to New York, and got my first job in film as a messenger and started learning.”

Craven learned quickly and within a year-and-a-half was rewarded with the opportunity to make his first film, The Last House on the Left, with producer Sean Cunningham, who later directed the first in the seemingly endless Friday the 13th (1980) series.

“At that time Sean had just finished his first small film, although he had never made a feature, and I had never written, directed or cut a film before, and I did all three on Last House. We just went off and made what we thought would be a very scary film, as that is what we had been asked to make by Hallmark Releasing, who were looking for a horror movie to show in their theatres, and thus we became horror film makers. But, before that time, I swear to god that neither one of us was an aficionado of horror, or knew much about it, or ever thought that we would be making them.”

Despite his early successes, Craven had to wade through a bog of big screen failures, Deadly Blessing (1981) and Swamp Thing (1982) among them, before conquering the planet in 1984. The film was A Nightmare on Elm Street, the villain a spectral child molester by the name of Freddy Krueger, and suddenly the thought of sleeping scared the hell out of millions of teenagers worldwide. A parade of sequels, a television series and a flurry of merchandising followed, making Robert Englund’s Freddy Krueger as powerful an icon of the Eighties as Connery’s Bond was of the Sixties. So how do you go about creating an icon? How could a character like Freddy Krueger become so popular?

“I think he’s a very solidly constructed character and, if I do say so himself, he was very powerful and original. I don’t think anybody had seen anyone quite like him before,” explained Craven.

“Freddy inhabited a world that had not been properly explored or presented before, certainly not for many years. I can’t think of another character who has inhabited nightmares and drawn the characters and the audience into that world of dreams in a coherent, exploratory way. It was the opening of a whole new door, a door that people have gone through for eons, but which had not been represented in the arts very well.”

Regardless of their grisly subject mater, Craven’s best movies are distinguished by their wicked sense of humour. “When I make a film it pretty much expresses where I am at that particular moment, and I’m at a period in my life when I’m feeling a lot more humour than I can express, so it makes its way into my films. It’s particularly evident, I think, in the Scream series.”

Craven appeared to be softening, albeit just a little, later in life. But is that what he really wanted? “I have become a little bit more civilised, and I’m not saying this is a good thing, it’s just what has happened. There were some very strong reactions against The Last House on the Left, against the explicit and protracted violence, and the ugliness of it. Since then I have moved towards being a little bit more abstract in the use of violence. Having an overall tone of violence rather than showing specific acts. To be honest, I’ve never been sure if that’s right or wrong.”

Craven certainly knew his mind regarding critics who describe his films as gratuitous. “I’m talking about violence, it’s not like the violence is irrelevant. If it were there simply to amuse I could understand, but I’m dealing with violence and violent people - how they operate and act and talk - so I don’t see how it could be gratuitous.”

Though frustrated at having to work almost exclusively within the horror genre, Craven acknowledged that they were the only films that allowed him complete artistic control, and since that was what he wanted most of all, he eventually made his peace with being pigeonholed.

“The strange thing about horror films is that they can be made on a very low budget and they afford a great amount of freedom, so there are two courses you can take once you become successful. The first is to pass over into mainstream culture and begin making films for other people, although there is some difficulty with that as horror films have a very real taint and a lot of people will not entertain the idea of working with you. They think you’re some sort of a Charles Manson.

“The second course is to continue making horror films because you’ll have the freedom to do what you want and you can become a sort of auteur within this forbidden, outlaw region of film, which some people think is terrific, and others believe is the work of the Devil! Well, that’s what happened to me.”

Which of Craven’s films would you say affected you most deeply?